'Unless the Water is Safer than the Land'

10.2017 – 11.2017

“Over the course of four weeks, twenty MA students conducted in-depth research into Australia’s immigration policies and practices at sea, producing spatial and visual analysis that reveals a striking pattern of human rights violations taking place off the coasts of Australia.

The Live Project was conducted in partnership with the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN), whose February 2017 communication to the International Criminal Court (ICC) called for the launch of an official investigation into the abuse of asylum seekers in offshore detention facilities in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. The aim of this collaboration is to provide GLAN with further elements of evidence that would allow it to continue addressing the legality of Australia’s immigration policy before and beyond the camps, and to push the Court into shifting its focus from ‘spectacular’ violence to ‘banal’ or ‘normalised’ violence that appears as an inevitable by-product of global social and economic structures.

In investigating and reconstructing these events, students developed creative forensic methodologies to cross-reference already available research when available and in particular to overcome the overall lack of information, which is a consequence of the Australian government’s policy of “on-sea” secrecy. Their work also involved tracking and exploring the development of particular patterns of practice at sea and situating these patterns in relation to the shifting political context in which they occurred, as well as inserting them within the longer histories of settler colonial violence.” – Opening excerpt from ‘Unless the Water us Safer than the Land’

A Place of Safety?

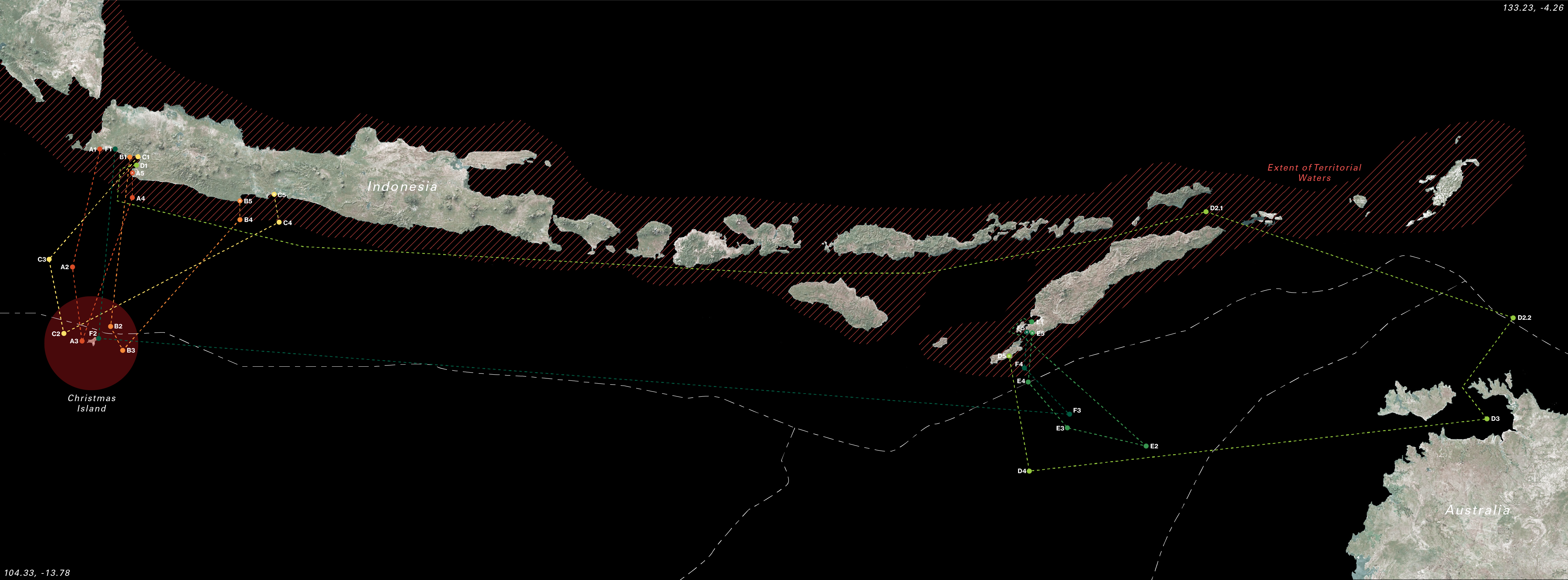

A critical analysis of Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders (OSB) policy during the January – February 2014 period.

In 2014, the Australian Navy implented the use of adultered lifeboats to turnback asylum seekers towards Indonesia. In accordance with international law, with regards to rescues at sea,this investigation asks a crucial question: Did Australia adequately ensure migrants reached a ‘place of safety’ after their interception and detainment by the Australian Navy?

Video footage taken by asylum seekers during journey back to Indonesia.

Introduction

This investigation concerns three turnback cases conducted under Operation Sovereign Borders (OSB) in the period between January and February 2014 (Cases 38, 39 & 40) in which three orange semi-submersible lifeboats were mobilised by the Australian navy, where the act of refoulement was imposed on a vulnerable population of asylum seekers and refugees back to the edge of Indonesia’s territorial waters. A seperate investigation (Cases 51, 56 & 60), is elaborated upon further in the full publication and examines the material shift in the Australian government’s strategy to utilise fishing vessels.

Our inquiry operates at two scales – the micro(interior) of the lifeboat and the macro(exterior) of the Indonesian drift waters and mainland. The former forms a speculation on the in-built functionality of the lifeboat as designed by the architects of OSB, the latter opens out a series of questions regarding the extent and spatial stretch of Australia’s responsibility to the asylum seekers and refugees under conditions of effective control.

Our legal argument focuses on the ‘place of safety’. International law requires that a rescue operation is terminated at a ‘place of safety’, defined as “a location where the rescue operation is considered to terminate [and] a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met” (IMO Resolution, MSC.167 (78)/26). In key, we contend that Australia’s strategy of covertly releasing lifeboat vessels on the edge of Indonesia’s territorial waters with inadequate on-board supplies operates in direct contravention to this. As with the previous section (Riski 02), we further contend that the on-board conditions of the lifeboat vessels operate by a detentive logic designed to deprive and deter a vulnerable population from not only entering Australia on the present occasion but all future potential occasions. This detentive design is then further explored in the metastasising of a shifted strategy of procurement, position and typology to fishing vessels for more covert operational means.

Legal Framework

Our legal argument focuses on the ‘place of safety’. International law requires that a rescue operation is terminated at a ‘place of safety’, defined as “a location where the rescue operation is considered to terminate [and] a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met” (IMO Resolution, MSC.167 (78)/26). In key, we contend that Australia’s strategy of covertly releasing lifeboat vessels on the edge of Indonesia’s territorial waters with inadequate on-board supplies operates in direct contravention to this. As with the previous section (Riski 02), we further contend that the on-board conditions of the lifeboat vessels operate by a detentive logic designed to deprive and deter a vulnerable population from not only entering Australia on the present occasion but all future potential occasions. This detentive design is then further explored in the metastasising of a shifted strategy of procurement, position and typology to fishing vessels for more covert operational means as seen in cases 51, 56 & 60.

'Place of Safety'

International law requires that a rescue operation is terminated at a ‘place of safety.’

QUESTIONS / FRAMEWORK FOR INVESTIGATION:

In order to properly address the question “Did Australia adequately ensure migrants reached a ‘place of safety’ after their interception and detainment by the Australian Navy?” We examined the continually changing conditions asylum seekers were subjected to before they reached a ‘place of safety’ in Indonesia. To answer the previous question, we asked two further questions:

i.

ii.

CASE 38 (A)

Date:

15-01-2014

Location:

Cikepuh, Indonesia

Number of Migrants:

56 pax.

Australian Ships:

HMAS Stuart &

HMAS Maitland

Asylum seekers told journalists that they set out for Christmas Island by boat from an island off the coast of Java on the 5th of January 2014. There were 56 aboard the boat including one woman and a toddler. After three or four days at sea, having been seen by an Australian aeroplane they scuttled their leaky boat to avoid being turned back to Indonesia like other asylum boats they knew of. They were rescued from the water by HMAS Stuart, transferred to a Customs vessel and ‘tricked’ into thinking they were being taken to Christmas Island. After five days in Australian custody the group were transferred to a small lifeboat and told they only had enough fuel to return to Indonesia; they were reportedly left three hours sailing time from the Indonesian shore. The Indonesian crew deserted the lifeboat in sight of land and the asylum seekers steered the vessel into shore, crash landing on a coral reef on a deserted beach in the remote area of Cikepuh on the 15th of January. The returnees made a perilous journey through the jungle on foot to reach safety. An Iranian couple in Cisarua told journalist Paul Toohey that they had been visited by a group of survivors from this voyage on the 17th of January who told them that ‘three people died while crossing a river in the jungle’ during their trek back to safety. Two asylum seekers who were returned to Indonesia on the lifeboat told Al Jazeera reporter Step Vaessen that they were left in the water for two and a half hours in sight of Navy vessels before being rescued.

CASE 39 (B)

Date:

05-02-2014

Location:

Pangandaran Bay, Indonesia

Number of Migrants:

34 pax.

Australian Ships:

HMAS Bathurst

& ACV Triton

Indonesian media reports state that on the 26th of January 2014, a group of 36 asylum seekers including 11 women – one of whom was pregnant – and at least two young children aged less than five years old, set sail from the south coast of West Java for Christmas Island. They were at sea for about 36 hours before they were intercepted by OSB close to Christmas Island on the 28th of January. Sometime after interception, they were herded into a navy vessel and their boat reportedly sunk by Australian officials. Australian media reports concerning this group of asylum seekers began in late January with claims that people were being held on HMAS Bathurst and that an orange lifeboat was being towed by ACV Triton several miles off Christmas Island. The lifeboat was reportedly towed near Christmas Island for at least five days, from the 29th of January to the 3rd of February. During this time it was reported that two men – asylum seekers on one of the Navy vessels – had been hospitalised, one on the 31st of January ‘for urgent medical treatment in relation to a heart condition,’ and a second man on the 3rd of February. It appears that the remaining 34 asylum seekers from this group were transferred into an OSB lifeboat (capacity 90 persons) on the morning of the 5th of February and towed back to Indonesia by an Australian navy vessel, arriving in Pangandaran Bay the same evening. People returned in the lifeboat told the Indonesian media that there had been some kind of physical altercation (presumably with Australian OSB personnel) and that they believed two men in their group died – presumably the two men referred to above who were removed to Christmas Island for medical treatment.

In March of that year, George Roberts attempted to discover the current whereabouts of these two men (named Ali & Hossain) but was unsuccessful. The asylum seekers also made video recordings inside the lifeboat on the journey back to Indonesia, which they subsequently provided to the media. A transcript of this video recording indicates that some of the group may have been turned back to Indonesia on a previous vessel and that one of them may have died in the jungle trying to reach safety. The transcript also suggest that this vessel was SIEV 879. That same month, Roberts interviewed people returned to Indonesia on this lifeboat for the 7.30 report and discovered that an Iranian couple Arash & Azi Sedigh had also been returned on another lifeboat on the 15th of January. This report by Roberts also included another video recording made inside the lifeboat. The lifeboat was reportedly manufactured in China by Jiangyinshi CO.LTD Beihai LSA, 33 # Beihuan Road, Yuecheng Town Jiangyin City 214 404 JIANGSU Province of China.

CASE 40 (C)

Date:

24-02-2014

Location:

Kebumen, Indonesia

Number of Migrants:

26 pax.

Australian Ships:

HMAS Bathurst

& ACV Triton

According to Indonesian media reports, 26 male asylum seekers varying in ages between 17 and 35, departed Pelabuhan Ratu for Christmas Island on the 19th of February. The group was comprised of people from Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan and the United Arab Emirates. The asylum seekers were reportedly at sea for three days and three nights before they were intercepted by the Australian Navy near Christmas Island. They were taken on board a Navy vessel and their boat was destroyed at sea. They were transferred to an OSB lifeboat (capacity 55 persons) close to Indonesia and left to make their own way back to land. The boat was found washed up on rocks at Kebumen on Monday, the 24th of February about 1pm local time.

i. Can an adultered, disposable, lifeboat truly be considered a 'place of safety'?

‘Place of Safety’: “A location where the rescue operation is considered to terminate. It is also a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met” (IMO Resolution, MSC.167 (78)/26)

‘Place of Unsafety’: A location where the rescue operation is not considered to terminate. It is also a place where the survivors’ safety of life is still threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) cannot be met (Formative Definition).

A policy of leaving rescued persons in unseaworthy boats on the high seas is inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under SOLAS to deliver rescued persons to a place of safety through coordination and cooperation with other States. In the cases 38, 39 and 40, the Australian navy operated in direct contravention of this. Here, we again open out the lifeboat vessel as an offshore detention facility with inbuilt deterrent design functionality and examine it against the recommendations of the landmark Hirsi Al-Jamaa and Others v. Italy ruling for the naval interceptor to:

9.3. GUARANTEE for all intercepted persons humane treatment and systematic respect for their human rights, including the principle of non-refoulement, regardless of whether interception measures are implemented within their own territorial waters, those of another state on the basis of an ad hoc bilateral agreement, or on the high seas;

9.4. REFRAIN from any practices that might be tantamount to direct or indirect refoulement, including on the high seas, in keeping with the UNHCR’s interpretation of the extraterritorial application of that principle and with the relevant judgments of the European Court of Human Rights;

9.5. CARRY OUT as a priority action the swift disembarkation of rescued persons to a “place of safety” and interpret a “place of safety” as meaning a place which can meet the immediate needs of those disembarked and in no way jeopardises their fundamental rights, since the notion of “safety” extends beyond mere protection from physical danger and must also take into account the fundamental rights dimension of the proposed place of disembarkation;

9.6. GUARANTEE access to a fair and effective asylum procedure for those intercepted who are in need of international protection.

Against this criteria, particularly points 9.5 and 9.6, the legal frame re-focuses to an analysis of conditions, thresholds and (dis)proportions surrounding the lifeboat vessel as the Australian navy’s designated place of disembarkation and takes as its courtroom model a 3D prototype of the lifeboat vessel (Model: Vanguard Lifeboat – VG8.5C; Dimensions (L x B x D): 8.5m x 3.2m x 3.3m Capacity: 85, Speed: 6 Knots / 11 km/h, engine: 60L; ‘Spares Removed’) in order to reconstruct Australia’s crime of detention, negligence and non-innocent offloading at an arbitrary place of unsafety. The parameters of investigation are legion and could concern: food, fuel-cap, water, screening platform, medical needs, seamanship skills, prevailing sea conditions, and weather conditions. From the small openings of our research, what does appear recurrent is a signature arbitrary calculus and negligence of the possible outcomes to a vulnerable population cut-loose on high-seas with inadequate supplies and vessel capability as part of an ongoing and common plan to deny, deprive and deter the fundamental rights of its subjects by design.

The following is stated in the UNHCR’s Practical Manual for Monitoring Immigration Detention: “By depriving a person of their liberty, the State assumes responsibility for providing for that person’s vital needs.” It is incumbent on the State to mitigate the loss of liberty as far as possible by ensuring that the detention environment and conditions are respectful of the dignity and non-criminal status of immigration detainees. Further, care needs to be taken in the design and layout of the premises to avoid as far as possible any impression of a carceral environment. This means that both the detention environment and the living conditions must be decent in every respect. Against this criteria, what emerges in the design and utilisation of lifeboats by the Australian state is a thoroughly planned and executed operation to ‘avoid as far as possible any impression of a carceral environment’ while simultaneously ‘arbitrarily detaining and depriving persons in that very position.’ In doing so, what are taken are direct measures to misleadingly deflect and covertly work around its international obligations in an ongoing and common plan which we believe thereby holds sufficient gravity to admit to the apparatus of the ICC. Our research also then extends to a question of where Australia’s responsibility for a vulnerable population under its effective control terminates if the place of disembarkation is itself terminally deferred to the high seas and not a Port or terminal where ‘protection from physical danger and the fundamental rights dimensions’ of the individual are met (non-refoulement). What emerges is a spatial narrative of places of unsafety: terminally deferred. By thereby opening out and re-constructing the series of events that emerge once the Vanguard vessel is released on the edge of Indonesian territorial waters, a case of negligence as first-order (cutloose), second-order (crash-land), third-order (trek) and fourth-order (Indonesian refugee detention camp, refouled) places of unsafety, terminally deferred and endured is brought against the Australian government, whereby the ‘extra-territorial reach of [its] human rights obligations’ (Goodwin-Gill, 2010) is thrown into sharp, prosecutive relief against its shortfalls.

ii. Can the seemingly indiscriminate sites at which these lifeboats 'crashlanded' be considered a 'place of safety'?

CRASHLAND SITES

In the cases recorded here of CASE 38, CASE 39 and CASE 40, the probabilistic zones of release/vessel cut loose are identified from a triangulation of survivor trace memory, archival media and the identifiable boundary of Indonesian territorial waters where offloading was most likely (CASE 38: ‘3 hours from Cikepuh; CASE 39: ‘33km out’). (Although not included here, an aggregation of oceanic drift models, meteorological data and satellite imagery would add further weight to the model). The probabilistic zones of crash landing are identified by cross-matching media releases with google earth data (Case 38: Remote Cikepuh; Case 39: West Coast of Pangadaran Bay, West Java; Case 40: Bay near village of Kebumen). From this, a case of first-order and second-order on-water negligence begins to construct itself.

By then further opening out the evidential inquiry to the conditions of the landing site – its topography and topological proximity to inhabited areas/hospitals/police stations – the case extends to enfold the outcomes of the Australian state’s on-sea negligence as off-sea effects of third-order (trek) and fourth-order (Indonesian refugee detention centre) direct culpabilities.

The diagrams that follow are preliminary openings into the parameters of such research and might be examined in line with the case brought against the Australian state for refouling a vulnerable population to a non-signatory state to the Refugee Convention in which Human Rights Watch reports have recently disclosed how:

Immigration authorities and Indonesian police arrest migrants and asylum seekers either as they cross into Indonesia or as they move towards the boats to Australia; NGOs and asylum seekers have also reported arrests in the areas outside Jakarta where many migrants live. Indonesian authorities routinely detain families, unaccompanied migrant children, and adult asylum seekers for months or even years in informal detention facilities and formal Immigration Detention Centers (IDCs). Migrants, including children, are typically detained without judicial review or bail, access to lawyers, or any way to challenge their detention.

The crashland site for case 39 was located on the eastern coast of the West Java province, outside the small village of Cijulang. While the boat crashed in a populated area, the nearest major medical clinic is located 40 km away. The journey there consists of steep uphill climbs, with flat stretches, through dense jungle.

This case had the ideal circum-stances of the crashlandings that were examined. The site of the crash is near a fishing village and the nearest hospital is 15 km away. However when considering the diagram on the left showing possible trajectories of the life vessel, other outcomes were very probable.

Case 51’s crashland site was located on the tip of peninsula-like landmass on the east coast of East Timor. The crashland site set travelers 22 km from the nearest hospital and put them in a condition where they would have had to traverse an initial 180 m steep uphill climb through medium-dense jungle.

In the final case examined, the crashland was located on a smaller island just southwest from the crash location of case 51. This small island is less populated than Java and East Timor, and covered in large areas of medium-dense foliage. The crash land was located 34.5 km from the nearest hospital, the first half being a steep uphill climb.

HOSTILITY

OF THE COASTLINE

Because crashlandings occur on the coast at 0m elevation, there is always an uphill climb required to search for social services, flee police, etc. While much of the southern Indonesian coast is covered with small fishing communities, these communities don’t have the social services necessary to process asylum seeker claims and treat serious injuries. We suggest many if not all of these small communities would not be considered a place of safety. Many coastal stretches highlighted below and on the right, show consistent areas of light to dense jungle which could hinder asylum seekers in their search for a place of safety.